Shockwave therapy differentially stimulates endothelial cells: implications on the control of inflammation via toll-like receptor 3

Abstract—Shock wave therapy (SWT) reportedly improves ventricular function in ischemic heart failure. Angiogenesis and inflammation modulatory effects were described. However, the mechanism remains largely unknown. We hypothesized that SWT modulates inflammation via toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) through the release of cytosolic RNA. SWT was applied to human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) with 250 impulses, 0.08 mJ/mm2 and 3 Hz. Gene expression of TLR3, inflammatory genes and signalling molecules was analysed at different time points by real-time polymerase chain reaction. SWT showed activation of HUVECs: enhanced expression of TLR3 and of the transporter protein for nucleic acids cyclophilin B, of pro-inflammatory cytokines cyclophilin A and interleukin-6 and of anti-inflammatory interleukin-10. No changes were found in the expression of vascular endothelial cell adhesion molecule. SWT modulates inflammation via the TLR3 pathway. The interaction between interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-10 in TLR3 stimulation can be schematically seen as a three-phase regulation over time.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory processes play an important role in

post-infarction myocardial remodelling. Adequate repair

after loss of a large amount of cardiomyocytes requires a

balanced response between inflammatory and regenerative stimuli [1]. Pro-inflammatory response is needed to

replace ischemically harmed necrotic tissue. Anti-inflammatory processes are required for limitation of inflammation and initiation of repair. Balanced inflammatory

response therefore is prerequisite in myocardial ischemia

to enable regeneration and angiogenesis [1].

Shock wave therapy (SWT) has been developed as a

standard of care or alternative treatment for a variety of

orthopaedic and soft tissue diseases, including ischemic

heart disease [2–6]. SWT was described to induce

suppression of the pro-inflammatory response in severe

cutaneous burn injuries in mice by potently attenuating

acute pro-inflammatory cytokine expression and extracellular matrix proteolytic activity at the wound margin [7].

Cardiac shock wave therapy has been repeatedly

described to improve left ventricular function in ischemic

heart disease [3, 8, 9]. This effect may largely be due to

the induction of angiogenesis [10]. In chronic myocardial

ischemia in rats, our group showed ameliorated heart

function and lower serum levels of BNP after direct epicardial SWT [11]. These beneficial findings could be

reproduced in a large animal model in pigs (unpublished

data). However, the mechanism of how the mechanical

stimulus of shock waves is translated into a biological

response remains unknown [12]. It was suggested that

SWT leads to an increase of cell membrane permeability[13]. Thereby, it could cause the release of cytosolic RNA.

In the present experiments, we therefore hypothesized that

SWT may modulate inflammation via stimulation of tolllike receptor 3 (TLR3). TLR3 is part of the innate immune

system and involved in the recognition of double-stranded

RNA (dsRNA) and fragmented deoxyribonucleic acid

(DNA) from viruses [14, 15]. It therefore could be able to

detect released cytosolic RNA from neighbouring cells.

TLR3 activation is characterized by an early pro-inflammatory phase and a late anti-inflammatory response. This

balancing may create the environment for angiogenesis

and repair in ischemic tissue [16].

RNA Isolation and PCR

RNAwas isolated from homogenized HUVECs using

TriReagent solution (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) according to

the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthesized using

iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA).

Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR (Applied Biosystems, USA) and the following oligonucleotides: huCYPA forward (forw.) GGCCAGGCTCGTGCCG TTTT, reverse (rev.) AAAGGAGACGCGGCCCAAGG; huCYPB forw. AGCTGTCCGGGCTGCTTTCG, rev. CTCATCGGCCGCAGAAGGTCC; huTLR3 forw.

ATGCTCCGAAGGGTGGCCC, rev. TGGGACCACCA

GGGTTTGCG; huIL-6 forw. ACCCCCAGGAGAAGA

TTCCA, rev. CAATTGCTTCTGAAGAGGTGAGT;

huIL-10 forw. GAGGCTACGGCGCTGTCAT, rev.

CCAGAGCCCCAGATCCGA; huVCAM-1 forw.

GCGAGGGTCTACCAGCTCCA, rev. ATCCGGGGT

CCAGGGGAGAT; and hu Tie-2 forw. CCAGCCCTGCT

GATACCAAA, rev. ATGTGCATGAGGTCCCAAGG.

Briefly, after a denaturation step at 95 °C for 10 min, the

cycling started. Annealing was performed at 60 °C for 10 s,

followed by a synthesis step at 72 °C for 25 s. SYBR Green

fluorescence was detected at 78 °C. After 40 cycles, the

experiment was finished by running a melting curve with

an augmentation of 0.3 to 95 °C followed by fluorescence

detection at the end of each augmentation step. The melting

curve was used to determine the specificity of the primer

pairs [18]. PCRs were performed in duplicate.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism® 5.02 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Results are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean. Controls were set to 100, and treatment groups are given as percent of control. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA followed by appropriate post hoc tests to confirm significance. Statistical significance was set to p<0.05.

Shock Wave Treatment

The electrohydraulic DermaGold® SWT therapy

system and the used applicator CG050-P (both TRT

LLC, Woodstock, USA produced by MTS Europe GmbH, Konstanz, Germany) were developed for the extracorporeal use of skin lesions. To apply shock waves properly to

the cells, the culture flasks were dunked into a water bath.

This water bath was built to enable further propagation of

shock waves after passing the cell culture as waves would

otherwise be reflected at the culture medium to ambient air

transition. Reflected waves then would disturb the upcoming ones. In addition, a V-shaped absorber was placed at

the back of the bath. The temperature of the water was

constantly held at 37 °C using a heater triggered by a

temperature sensor. Referring to our experience in animal models as well as to published data for skin lesions, we used 0.08 mJ/mm2 energy flux density and applied 25 impulses/cm2 cell culture flask in a frequency of 3 Hz (pulses per second).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

After obtaining written informed consent of patients,

umbilical cords were obtained from Caesarean section at the

Department of Gynaecology for isolation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). Permission was given

from the ethics committee of Innsbruck Medical University

(no. UN4435). Isolation was performed as described

previously [17]. Freshly isolated HUVECs were cultivated

in endothelial cell basal medium (CC-3156, Lonza,

Walkersville, USA) supplemented with EGM-2 SingleQuots

supplements (CC-4176, Lonza). Cells (4×105) were

suspended per T25 flask 12 h before treatment. Cells used

in these experiments all were in passage 5. Two culture flasks

were used for each group. Cells were harvested 2, 4 and 6 h

after SWT. The structural analogue to double-stranded RNA

polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (Poly (I:C) HMW,

InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) in a concentration of 200 μg/

ml served as a positive control for TLR-3 activation in

HUVECs.

RESULTS

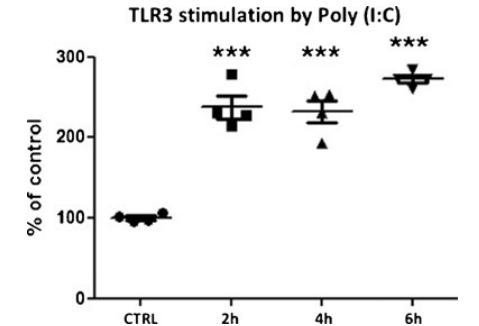

TLR3 Agonist Poly(I:C) Stimulates TLR3 on HUVECs

Polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (Poly (I:C)) serves as a synthetic, structural analogue to dsRNA. A concentration of 200 μg ml culture medium was used to asses time-dependent stimulation of TLR3 showing an early and highly significant effect after 2 h lasting for 6 h (agonist group 237.7±14.1 (2 h); 231.9±14.1 (4 h); 272.4 ±4.7 (6 h) vs. control, p<0.001) (Fig. 1). This confirms that TLR3 on endothelial cells can be activated by dsRNA and represents a positive control to shock wave stimulation for this experiment.

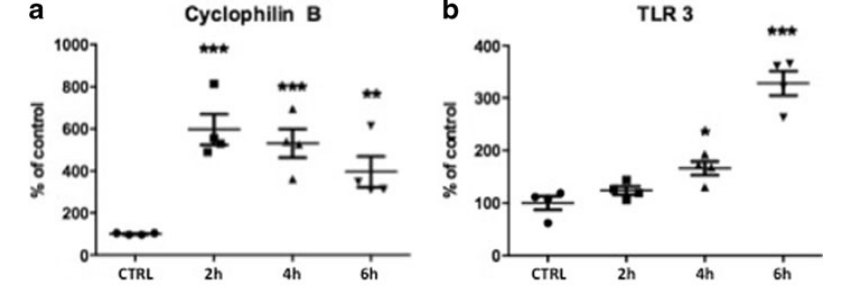

Cellular Uptake of Nucleic Acids and TLR3 Stimulation After SWT Cyclophilin B (CYP B) is responsible for the uptake of nucleic acids into cells. In the cytosol, it can bind to the TLR3 receptors, which are located on endosomes. Treated cells showed an immediate up-regulation of CYP B after SWT (SWT 597.39±59.84 (2 h), p<0.001; 527.84±68.16 (4 h), p<0.001; 424.73±67.13 (6 h), p< 0.01 vs. control) (Fig. 2a). An increased amount of the transporter protein CYP B is necessary to accomplish the cellular uptake of nucleic acids. CYP B expression decreases again as indicated after 6 h representing the depletion of the uptake process. In line with CYP B up-regulation, the expression of TLR3 mRNA was found to be significantly increased after SWT. As TLR3 up-regulates its expression by an auto-loop, after 6 h, the difference between untreated controls and therapy group was even more significant (SWT 123.78± 6.56 (2 h), p>0.05; 165.68±10.61 (4 h), p<0.05; 328.15± 19.33 (6 h), p<0.001 vs. control) (Fig. 2b).

Cellular Uptake of Nucleic Acids and TLR3 Stimulation After SWT

Cyclophilin B (CYP B) is responsible for the uptake of nucleic acids into cells. In the cytosol, it can bind to the TLR3 receptors, which are located on endosomes. Treated cells showed an immediate up-regulation of CYP B after SWT (SWT 597.39±59.84 (2 h), p<0.001; 527.84±68.16 (4 h), p<0.001; 424.73±67.13 (6 h), p< 0.01 vs. control) (Fig. 2a). An increased amount of the transporter protein CYP B is necessary to accomplish the cellular uptake of nucleic acids. CYP B expression decreases again as indicated after 6 h representing the depletion of the uptake process. In line with CYP B up-regulation, the expression of TLR3 mRNA was found to be significantly increased after SWT. As TLR3 up-regulates its expression by an auto-loop, after 6 h, the difference between untreated controls and therapy group was even more significant (SWT 123.78± 6.56 (2 h), p>0.05; 165.68±10.61 (4 h), p<0.05; 328.15± 19.33 (6 h), p<0.001 vs. control) (Fig. 2b).

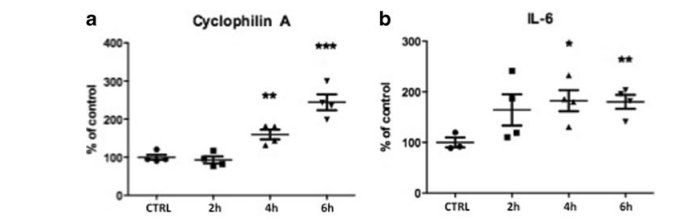

Initiation Phase: Pro-Inflammatory Response Mediated by Cyclophilin A and Interleukin 6

The TLR3 pathway is characterized by an early proinflammatory response mainly of interleukin 6 (initiation

phase). It is mediated by cyclophilin A (CYP A), which

further promotes the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin 6 [19]. Interleukin (IL)-6 itself serves as a chemoattractant to monocytes. Thereby, they get directed to the site of inflammation. In our experiment, we could find an up-regulation of CYP A (SWT 92.98±7.44 (2 h), p>0.05; 159.75±10.43 (4 h), p<0.01; 244.35±17.05 (6 h), p<0.001 vs. control) as well as of IL-6 (SWT 164.3± 25.19 (2 h), p>0.05; 182.2±17.06 (4 h), p<0.05; 180.23± 11.4 (6 h), p<0.01 vs. control) after SWT indicating the activation of an early pro-inflammatory response of the TLR3 pathway in the initiation phase (Fig. 3a, b).

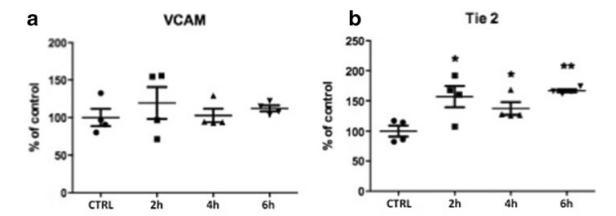

Middle Phase: Suppression of Inflammation

Vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM) is a

surface protein responsible for the mediation of leucocyte

adhesion and is therefore an indicator for prolonged

inflammation [20]. Although pro-inflammatory cytokine

IL-6 is increased, VCAM is not up-regulated in treated

cells compared to untreated controls (SWT 119.31±17.23 (2 h), p>0.05; 102.63±7.17 (4 h), p>0.05; 111.78±3.33

(6 h), p>0.05 vs. control) (Fig. 4a). This fact indicates that

IL-6 may not cause inflammation in treated tissue after

SWT. We therefore hypothesize that it rather serves as a

chemoattractant to monocytes. Thereby, it reveals the

modulation of TLR3-mediated inflammatory response

that results in a middle phase with beginning suppression

of inflammation.

Tyrosine kinase with immunoglobulin-like and EGF-like domains 2 (Tie2) represents a protein, which is expressed on endothelial cells only. Up-regulated Tie2 mRNA shows significantly enhanced proliferation in endothelial cells after SWT (SWT 154.25±16.39 (2 h), p<0.05; 137.23±8.52 (4 h), p<0.05; 166.68±2.15 (6 h), p<0.01 vs. control) (Fig. 4b). This finding shows that endothelial cells are in a physiologic condition and it therefore further supports the hypothesis of a balanced inflammatory response. It is in line with the nonsignifi

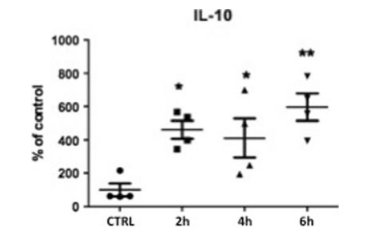

Limitation Phase: Late Anti-Inflammatory Effect Mediated by IL-10

TLR3 response is characterized by the late production of IL-10 marking an anti-inflammatory limitation phase. The expression of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL10 was significantly enhanced after SWT (SWT 460.9± 43.72 (2 h), p<0.05; 410.83±95.55 (4 h), p<0.05; 595.88 ±66.66 (6 h), p<0.01 vs. control) (Fig. 5). It seems to be responsible for limitation of the inflammatory regulation thereby creating the environment for tissue repair.

cant expression of VCAM at all time points. Moreover,

the suppression of inflammation may be indicated by Tie2

expression being slightly higher at later time points.

DISCUSSION

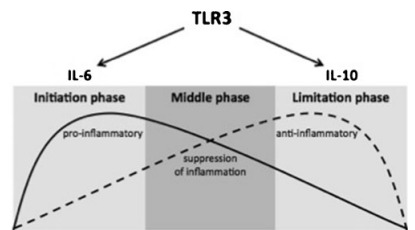

Low-energy shock wave treatment is well known to induce tissue regeneration and angiogenesis in ischemic myocardium. It has been proven in numerous animal models as well as in human pilot trials [4, 8–11]. Nevertheless, the underlying mechanism remains largely unknown. Modulation of inflammation is prerequisite for regeneration and angiogenesis as shown in a burn injury model in mice in which SWT potently attenuates cytokine expression at the wound margin [7]. In the present in vitro experiments, we hypothesized that SWT may modulate inflammation via stimulation of TLR3. TLR3 is part of the innate immune system and involved in the recognition of dsRNA and fragmented DNA from viruses [14, 15]. TLR3 activation is characterized by an early pro inflammatory and a late antiinflammatory response. This balancing creates an environment for repair and angiogenesis in ischemic tissue [16].

We first proved that TLR3 activation on endothelial cells is possible by using the TLR3 agonist

polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (Poly(I:C)). Then, we

exposed the cells to low-energy SWT and performed

analysis of the main inflammatory cytokines. Thereby, we

show that the complex interaction between the two main

cytokines IL-6 and IL-10 after TLR3 stimulation can be

schematically seen as a three-phase regulation over time

(Fig. 6). The different phases are of course overlapping.

After an early pro-inflammatory initiation phase mediated

by IL-6, a middle phase with beginning suppression of

inflammation can be seen. It finally results in a late antiinflammatory limitation phase of IL-10.

Preclinical studies show beneficial effects of antiinflammatory treatment after myocardial infarction by

decreasing the infarct size-to-area-at-risk ratio [21, 22].

However, these studies remain experimental as none of

them have been translated into clinic. Therefore, a safe

treatment option that modulates the inflammatory response

after myocardial infarction is of high therapeutic interest.

The results of our present study suggest that the

tissue regenerative effect of shock wave therapy is at least

in part mediated by TLR3 stimulation.

Nevertheless, further experiments are needed and a

trial with TLR3 knockout mice is on its way to reproduce

our current findings in vivo and prove the hypothesis.

In conclusion, we for the first time show that the effects

of myocardial regeneration by low-energy shock wave

treatment are at least in part by creating an environment for

regeneration and angiogenesis through modulating inflammation via toll-like receptor 3 stimulation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was in part funded by a research grant

from Bayer Pharma AG (Grants4Targets) to P.P. and by

Medizinischer Forschungsfonds Tirol (MFF) project no.

220 to J.H. The sponsors of this study had no role in study

design, data collection, analysis, and decision to publish

or prepare the manuscript nor have any financial interest.

Conflicts of interest. None

TLR3 stimulation can be schematically seen as a three-phase regulation over time. After an early pro-inflammatory initiation phase mediated by IL-6, a

middle phase showing suppression of inflammation can be seen before the late anti-inflammatory limitation phase of IL-10 results. This modulation of the

inflammatory response is prerequisite for angiogenesis and repair in ischemic tissue.

REFERENCES

- Nahrendorf, M., M.J. Pittet, and F.K. Swirski. 2010. Monocytes:

protagonists of infarct inflammation and repair after myocardial

infarction. Circulation 121(22): 2437–2445. - Haupt, G., A. Haupt, A. Ekkernkamp, B. Gerety, and M. Chvapil. 1992.

Influence of shock waves on fracture healing. Urology 39: 529–532. - Chen, Y.J., C.J. Wang, K.D. Yang, Y.R. Kuo, H.C. Huang, Y.T. Huang,

Y.C. Sun, and F.S. Wang. 2004. Extracorporeal shock waves promote

healing of collagenase-induced Achilles tendinitis and increase TGF-beta1

and IGF-I expression. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 22: 854–861. - Fukumoto, Y., A. Ito, T. Uwatoku, T. Matoba, T. Kishi, H. Tanaka, A.

Takeshita, K. Sunagawa, and H. Shimokawa. 2006. Extracorporeal

cardiac shock wave therapy ameliorates myocardial ischemia in patients

with severe coronary artery disease. Coronary Artery Disease 17: 63–70. - Wang, C.J., K.D. Yang, F.S. Wang, C.C. Hsu, and H.H. Chen. 2004.

Shock wave treatment shows dose-dependent enhancement of bone

mass and bone strength after fracture of the femur. Bone 34: 225–230. - Schaden, W., R. Thiele, C. Kolpl, M. Pusch, A. Nissan, C.E. Attinger,

M.E. Maniscalco-Theberge, G.E. Peoples, E.A. Elster, and A. Stojadinovic. 2007. Shock wave therapy for acute and chronic soft tissue wounds: a feasibility study. Journal of Surgical Research 143: 1–12.

- Davis, T.A., A. Stojadinovic, K. Anam, M. Amare, S. Naik, G.E.

Peoples, D. Tadaki, and E.A. Elster. 2009. Extracorporeal shock wave

therapy suppresses the early proinflammatory immune response to a

severe cutaneous burn injury. International Wound Journal 6(1): 11. - Wang, Y., T. Guo, H.Y. Cai, T.K. Ma, S.M. Tao, S. Sun, et al. 2010.

Cardiac shock wave therapy reduces angina and improves myocardial function in patients with refractory coronary artery disease.

Clinical Cardiology 33(11): 693–699. - Zuozienė, G., A. Laucevičius, and D. Leibowitz. 2012. Extracorporeal shockwave myocardial revascularization improves clinical

symptoms and left ventricular function in patients with refractory

angina. Coronary Artery Disease 23(1): 62–67. - Tepeköylü, C., FS. Wang, R. Kozaryn, K. Albrecht-Schgoer, M.

Theurl, W. Schaden, HJ. Ke, Y. Yang, R. Kirchmair, M. Grimm, CJ.

Wang, and J. Holfeld. 2013. Shock wave treatment induces

angiogenesis and mobilizes endogenous CD31/CD34-positive endothelial cells in a hindlimb ischemia model: implications for angiogenesis and vasculogenesis. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular

Surgery. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.01.017.

REFERENCES

- Zimpfer, D., S. Aharinejad, J. Holfeld, A. Thomas, J. Dumfarth, R.

Rosenhek, M. Czerny, W. Schaden, M. Gmeiner, E. Wolner, and M.

Grimm. 2009. Direct epicardial shock wave therapy improves

ventricular function and induces angiogenesis in ischemic heart

failure. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery

137(4): 963–970. - Kuo, Y.R., C.T. Wang, F.S. Wang, K.D. Yang, Y.C. Chiang, and C.J.

Wang. 2009. Extracorporeal shock wave treatment modulates skin

fibroblast recruitment and leukocyte infiltration for enhancing extended

skin-flap survival. Wound Repair and Regeneration 17(1): 80–87. - Martini, L., G. Giavaresi, M. Fini, P. Torricelli, V. Borsari, R.

Giardino, M. De Pretto, D. Remondini, and G.C. Castellani. 2005.

Shock wave therapy as an innovative technology in skeletal disorders:

study on transmembrane current in stimulated osteoblast-like cells.

The International Journal of Artificial Organs 28(8): 841–847. - Alexopoulou, L., A.C. Holt, R. Medzhitov, and R.A. Flavell. 2001.

Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-kappaB

by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature 413(6857): 732–738. - Takeda K, Akira S. Toll-like receptors. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2007

May; Chapter 14: Unit 14.12. - Chi, H., S.P. Barry, R.J. Roth, J.J. Wu, E.A. Jones, A.M. Bennett,

and R.A. Flavell. 2006. Dynamic regulation of pro- and antiinflammatory cytokines by MAPK phosphatase 1 (MKP-1) in innate

immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103(7): 2274–2279. - Siow, R.C. 2012. Culture of human endothelial cells from umbilical

veins. Methods in Molecular Biology 806: 265–274. - Paulus, P., E.R. Stanley, R. Schäfer, D. Abraham, and S. Aharinejad. 2006.

Colony-stimulating factor-1 antibody reverses chemoresistance in human

MCF-7 breast cancer xenografts. Cancer Research 66(8): 4349–4356. - Payeli, S.K., C. Schiene-Fischer, J. Steffel, G.G. Camici, I.

Rozenberg, T.F. Lüscher, and F.C. Tanner. 2008. Cyclophilin A

differentially activates monocytes and endothelial cells: role of

purity, activity, and endotoxin contamination in commercial

preparations. Atherosclerosis 197(2): 564–571. - Ross, E.A., M.R. Douglas, S.H. Wong, E.J. Ross, S.J. Curnow, G.B.

Nash, E. Rainger, D. Scheel-Toellner, J.M. Lord, M. Salmon, and

C.D. Buckley. 2006. Interaction between integrin alpha9beta1 and

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) inhibits neutrophil

apoptosis. Blood 107(3): 1178–1183. - Frangogiannis, N.G., C.W. Smith, and M.L. Entman. 2002. The

inflammatory response in myocardial infarction. Cardiovascular

Research 53: 31–47. - Steffens, S., F. Montecucco, and F. Mach. 2009. The inflammatory

response as a target to reduce myocardial ischaemia and reperfusion

injury. Thrombosis and Haemostasis 102: 240–247.

Johannes Holfeld,1 Can Tepeköylü,1 Radoslaw Kozaryn,1

Anja Urbschat,2 Kai Zacharowski,3 Michael Grimm,1 and Patrick Paulus3,4